Who gets in? Rethinking Admission — Confronting Segregation

Members of working group: Rose Brander, Andreas Engman, Inga Kolbrun Söring, Eva Weinmayr & Lucy Wilson

Right Arrow or swipe left to move to next slide.

Foreword

“The fundamental thing is that we are working to a limited demographic and we want to work to a wider demographic. That’s age, gender, race, class, ability and so forth. The problem I see is that this doesn’t change overnight, it is a long, non-linear process.”

(teacher) 1

“It is totally unacceptable that we have this repeating situation with only one or two or three students that are not white and middle class. We can’t go on like this, right? Also, we need to think about who the teachers are and where the programme is visible in society. It’s all connected.”

(teacher)

1. Introduction

The Context

Many critical voices have very bluntly asked if the Westernized university today is inherently racist and sexist. Our work looks into the concrete challenges of widening participation today and specifically focuses on the various admission policies currently in place. Admission policies are obviously pivotal in deciding who gets in and who’s left out. The topic is vast and entangled in questions of economic resource, public opinion, outreach priorities, cultural policy, national law, curriculum design and institutional profiling.

Looking at higher arts education institutions in Europe today, it is probably fair to say that they tend not to reflect societal demographics in terms of things like ethnicity, gender, age, ability, and class. This has been recognized and researched as a persistent problem in general, and as a sign that many educations, and education in the field of art in particular, are daily operating with and sustaining exclusionary mechanisms.

We chose the title “confronting segregation” because there seems to be a correlation between systematic exclusion when it comes to accessing art schools and segregation in general. “Segregation” is commonly understood as laws, customs, or practices under which different races, groups etc., are restricted to specific or separate public facilities, neighbourhoods, schools, organizations, etc. The way in which many institutions, intentionally or not, daily exclude different constituencies could be seen as having a segregating effect in society. Therefore, working towards opening up these institutions to better reflect society could be viewed as a form, or component of general desegregation.

Situated at

We situated this inquiry in the local context of HDK-Valand, Academy of Art and Design in Gothenburg. It was carried out over two years by the working group “Who gets in? Rethinking admission policies — confronting segregation” as part of the transnational European Teaching to Transgress Toolbox (TTTT) programme, a collective research and study programme to address questions of inclusive learning and teaching in the arts. One of several working groups formed during the two-year programme, this group initially consisted of Rose Brander, Andreas Engman, Inga Kolbrun Söring, Eva Weinmayr and Lucy Wilson. We set out to investigate how admission work is being done at our own institution, which we then inhabited in different roles: as graduating student, administrator, adjunct, and researcher.

We thought focusing on our local context and experiences working in a higher art education institution in Sweden’s second-largest city, Gothenburg, would be a good place to start — digging where we stand, so to speak. Understanding that we were conducting our research within the very particular place of this institution, we still hope that these local findings can be unpacked and applied to other contexts concerned with broadening participation today. We presume that we share a lot of the same struggles when it comes to this kind of work.

Informed by

This work has been greatly inspired by a study “Art School Differences — Researching Inequalities and Normativities in the Field of Higher Art Education” from the Institute for Art Education, Zurich (ZHdK) 2 Focussing on three Swiss art schools (ZHdK in Zurich, HEAD and HEM in Geneva), that project asked how processes of inclusion and exclusion take place and which discourses and logics accompany and frame such processes. Accordingly, the relevant question for “Art School Differences” was less whether inequalities and normativities are reproduced by art colleges, but rather how this happens, i.e., through which specific procedures, policies and discourses.

The study found, among many other insights, that people who have benefited from the support of their families or other mentors and have had teaching in art and music, or access to a social network in this domain, are very likely to succeed in accessing art school. We took a few questions that inspired our research from the final report (translated by the authors):

- Through which institutional policies and practices are inclusion and exclusion (re)produced?

- What tensions characterize the selection of candidates?

- Are there any specific mechanisms that lead to the exclusion of certain social groups?

- How are these processes connected to artistic fields and political and economic logics?

- To what extent do the practices of selection reflect the interrelationships of current local and global structures that are relevant to the artistic fields?

- With what biographies, strategies and motivations do the candidates approach art academies?

Lastly, the study asked:

- Can there be a critical or radical pedagogy in a field that is generally perceived as a ‘preserve of the privileged’”? And “what might such critical or radical pedagogies look like?” (Vögele, 2016)

2. Our Questions

Concretely

The TTTT working group wanted to understand how admission work is done at the art academy we are working in and in which ways admission differs between the different units, Fine Art, Craft, Film, Photo and Literary Composition? Here are some of the questions we started with:

- If admission work is done differently across units, why?

- Is there a common conversation across the different units addressing the structures and traditions that we inherit and that inform our practices?

- What are the obstacles for changing the inherited ways of doing things?

- How can we think about quota systems or affirmative action in the particular context of Gothenburg University, a state-run university that has strict equal treatment policies?

- How do we deal with the inevitable question of personal bias when looking at work samples and interviewing applicants?

- To what extent are we as individuals, and as a collective (institution) open to radically transforming our institutions to reflect the demographics of society?

3. Methods: Conversations, Roleplay

Conversations

We wanted to understand the rationales, practicalities, and obstacles in our own institution concerned with rethinking admission policies intersectionally and inclusively. Our method was recorded conversations with a number of BA programme leaders, or persons whom we knew had practical knowledge or were invested in the topic of widening participation. We focussed on Bachelor programmes because they are the entry point for people who want to study at university.

Many of the conversations were informal, speculative and personal, touching on conflicting and controversial topics. As a way of preserving the integrity of everyone's opinion and to care for the intimate space these conversations provided, we decided not to attach names to the written quotes.

Our conversations took place in summer 2021 with the following members of staff (post descriptors at the time):

- Behjat Omer Abdulla (Adjunct Lecturer Fine Art, River of Light,3 Open Up)

- Elisabeth Hjort (Programme leader, BA Literary Composition)

- Jeuno Kim (former programme leader, BA Fine Art)

- Nils Kristofersson (Programme leader, BA Craft)

- Nina Mangalanayagam (Programme leader, BA Photography)

- Linda Sternö (Programme leader, BA Film)

- Arne Kjell Vikhagen (Programme leader, BA Fine Art)

- Mick Wilson (Director of Studies, former head of department, Open Up4)

“River of Light” procession through Gothenburg town centre on United Nations Social Justice day, February 20, 2017. 3

“River of Light” procession through Gothenburg town centre on United Nations Social Justice day, February 20, 2017. 3

Roleplay

We also workshopped the (power) dynamics that unfold during an interview situation in a set of roleplays. That means the dynamics between the interviewer and the interviewees, but also among the jury members. We basically assigned ourselves the roles that normally make up an interview situation, such as applicant(s) and members of the jury, and played out a variety of possible (and sometimes unlikely) interview scenarios.

This helped us understand the impact of the spatial set-up, the room, the choice of furniture, the arrangement, etc. and how these arrangements inform the ways attendees relate to each other. We also staged online interviews, since these became standard in the years 2020–2021, due to COVID-19 restrictions.

Experimenting with different viewpoints and characters in these workshops, a kind of free-form acting, helped sharpen our questions. By playing the role of interviewers or interviewees, we became aware of and able to reflect upon a vast range of nuanced power dynamics.

Roleplay: Andreas Engman, Inga Kolbrun Söring, Eva Weinmayr: How do you deal with hierarchies in the group?, HDK-Valand, November 2020

4. The Swedish Context

Admissions solely based on merit and quality?

“The admissions process is not transparent: We don’t talk about the decisions we make in the jury. We’re not required to justify our decisions, though there are some rules that we have to follow. We’re not allowed to think in quotas for example. This is something that we follow to the letter.”

(teacher)

“We cannot use affirmative5 action here in Sweden. That is not allowed. We cannot look at the applicants' backgrounds like age, gender, class, whatever. So we have to be clever about what we ask for so that the interest of the applicants becomes visible through their texts and their artistic material. Many of the applicants applying know that we as an educational institution are looking for the perspectives missing in film today. So they are already practicing criticality when it comes to representation when they apply. They have a critical perspective even though the majority are white students. When it comes to class, it is more mixed.”

(teacher)

Universities in Sweden are run by the State, which, for the purpose of fair treatment, has introduced an admissions protocol solely based on merit as opposed to taking applicants’ gender, class, ethnicity, race, ability etc. into account. Important to note that in Sweden no tuition fees are charged for EU and EEA (European Economic Area) citizens, Swedish residence permit holders and exchange students.

Merit here refers to the quality of the portfolio rather than patronage, family relationships, wealth on the one side, or social skills, community orientation, gender equality, or diversity (age, class, ethnicity, cultural background) on the other.

All these factors must be excluded from informing the selection process. Failure to do so can result in legal action, as a case at Uppsala University demonstrates: the institution introduced a quota of 30 places out of 300 for law applicants with both parents born outside Sweden. Two rejected Swedish-born students who had better grades, than some of those admitted, argued that their ethnic background was a factor they could not influence (i.e., where their parents were born), and, claiming to be victims of unfair treatment, sued the university. Both the lower courts and Supreme Court ruled in their favour.

How do we account for differences within the meritocratic dream of assumed equality?

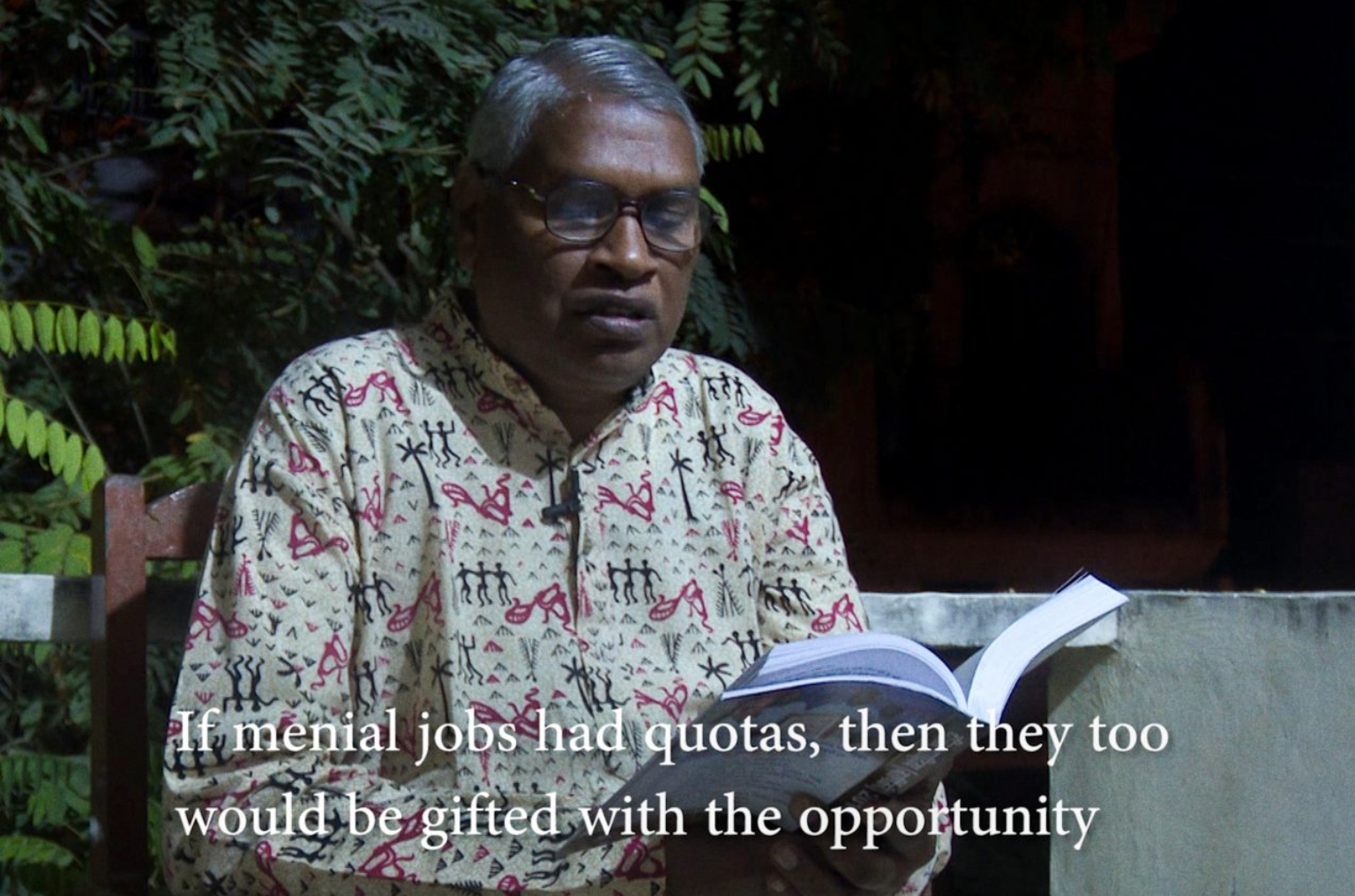

"Students appeal against positive discrimination". This video is part of a larger body of work by Ram Krishna Ranjan titled “Reservation: One or Two Stories?” The work consists of a multi-channel video installation and documents exhibited as part of HDK-Valand’s MFA degree show at Göteborg Konsthall, 2017.

Shifting the epistemic and social location from Sweden to India and Brazil

Ram Krishna Ranjan, video still, multi-channel video installation “Reservation: one or two stories?” 2017

Ram Krishna Ranjan, video still, multi-channel video installation “Reservation: one or two stories?” 2017

Ram Krishna Ranjan's multipart installation at Göteborg Konsthall was an attempt to produce a layered examination of questions around equality and social justice by shifting the geographies of reason (and being) from Sweden to India where positive action is politicized as a right via India’s constitution. He writes:

Evidently, there are systems of affirmative action in place around the world to tackle systemic inequality and exclusion. Filmmaker and educator Cecilia Torquato (2018), for example, introduces us to the quota system used in Brazil, asking if this model of affirmative action might offer us a different angle on admissions policies in Sweden.

The Swedish legal system has deemed these strategies discriminatory, but can we use these examples to problematize Sweden’s possibly over-confident belief in meritocracy and imagine new structures and procedures for admissions?

Cecilia Torquato (2018, 1–2) writes that the former Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff signed in 2012, the “Law of Social Quotas” requiring the public universities in Brazil to reserve half their admission places for students who attended a Brazilian public school. The intention was to promote access for people of colour, indigenous descendants and people with low incomes to higher education and thus give underprivileged and historically excluded groups access to good-quality, free higher education. The University in Rio had already in 2003 implemented such a quota system as a pilot scheme, and two other universities — both state and federally funded — had implemented it in 2004 and 2005.

The Brazilian system of admissions to higher education is based on an entrance exam. Before the introduction of quota, mostly students whose parents could afford private education scored high in the exams and therefore got admitted.

“In a country where most of the population is poor, where blacks and indigenous people have inherited poverty from slavery and white exploitation, and where public secondary schools and public high schools are poorly resourced and lack of quality, this was extremely unfair. It maintained the status quo of privilege under the flag of meritocracy.” (Torquato 2018, 2)

Swedish Context: Small student numbers

“We don’t agree in the collegiate [faculty], so I’m just speaking for me. I would rather prefer to see a larger student group that can develop collective work than six individuals. I would propose a group of around 10-12 students. This of course would mean that we would have to change how the programme is being taught.. And if we would be making this change it would have to be a step-by step process to have every teacher on board.”

(teacher)

Another specificity in the Swedish context is the very limited number of students forming the year groups. The number of students in each normally varies from around 6-18 in the programmes we examined (Film, Photography, Fine Art, Literary Composition, Craft). This leads to very exclusive and possibly elitist educations in terms of access and representation.

There is an ongoing conversation in Sweden about the relationship between student numbers and broadening participation. This also links to the institutions’ economic resources and student place numbers the State recognizes as viable for each subject. The question becomes: how many artists should we educate in Sweden at the moment? This makes the discussion on student groups pretty tricky. What actually decides the number of students in the year groups? The answer wasn’t obvious to the educators we talked to.

One teacher said they had around 15 students in each year group and that was about what they could manage with the resources they had. Another educator working with a small number of students problematized the imbalance of the teacher team being bigger than the student body, saying this may lead to a weaker collective student voice with regard to student rights, for example (critical mass). It also seems quite difficult to build a multi-vocal critical environment with only six students in one BA year group because the quantity and diversity of voices is so limited.

Swedish Context: Prep school tradition

“It’s very common that the students entering our programmes have multiple years of preparatory education when they enter. This gives us a flying start compared to other educational institutions in Europe, for example. But the prep schools are also a huge problem. It’s the filtering that goes on before students even apply to university. And also, applicants believe this is the only way into the art school.”

(teacher)

“If we imagine the preparatory schools disappearing overnight, I think that would mean we would have to introduce a base year for the first five years because at the moment our educational approach is not tailored to students with no preparatory education.”

(teacher)

New art school applicants commonly have had somewhere between one and three years of preparatory education. This has financial implications: tuition fees, material costs and the students just being out of employment during attendance.6

It was widely recognized among the interviewees that the assumed need for preparatory education problematically narrows access opportunities. Many programmes in recent years have tried to state clearly that applicants do not need to have gone through preparatory education, but prep schools seem to persist as a route that applicants take.

And some programmes seem to rely on this. They argue that for the students to be able to start work, they need to know about and be skilled in their specific medium, and this is tested in interviews and through work samples. Such programmes have designed their syllabus to correspond to the skill level of these previously trained incoming students.

The current curriculum would require a major revision to accommodate students with less skills and preparatory education. There would also likely be discrepancies in knowledge between students who have gone to a preparatory school and those who have not.

This would create new demands on the teaching. So are teaching staff prepared to take on the extra work when less homogenous student groups enter institutions? Are juries prepared to challenge the normative assumption of what kind of pre-established knowledge one needs? Are teachers willing to broaden their own assumptions and habits when deciding which ways of working are legitimate?

TO CONSIDER: What kind of student experience do we want in our school?

“We should not only be looking for one thing, we’re looking for lots of different constellations of skills and abilities and interests.”

(teacher)

“When applicants talk about their experience in the letter of motivation, it can be anything from someone conducting writing courses in prisons like last year, or someone that heard something on the radio, or went to a poetry slam thinking this is something I’m interested in. All those experiences are something we can build upon and use when we teach from the position that we are each other's resources. We need all sorts of experiences. But we can be clearer about signalling that all kinds of experiences are counted, so to speak.”

(teacher)

TO CONSIDER: What kind of artistic practitioners do we want our institution to “produce”?

"It is interesting because we’re talking about this a lot in terms of, do we want to make a photography education that is giving you skills that you can take with you in work life? At the moment it’s very much to become an artist, but there are not very many jobs as an artist, and it’s also very abstract what that means. I think we have a reputation of being too academic. It’s a little bit of a hot potato in the collegiate [faculty] at the moment, figuring out what we as an educational programme want to be.”

(teacher)

"Historically the education has been very focused on producing the individual auteur. Before it was almost as if each individual had their own education.”

(teacher)

“For certain people it is really important that you be able to make money after your education and that is something we need to think about. There are no guarantees, but to create a programme that actually has contact with people who are working as literary critics, translators, well everything that possibly could mean a way to survive afterwards, that is important.”

(teacher)

5. Selection Criteria

“Artistic Quality”

In a study published in 2018, scholar and filmmaker Cecilia Torquato points out that it is mostly the “artistic suitability” and “artistic talent” of the applicant that decides whether they’re admitted to art schools in Sweden. She refers to a study by Martha Edling, et al. (2012):

“…it is the artistic suitability; ‘the artistic talent' [that] is crucial for the applicant to be selected at the most distinguished institutions of art education in Sweden. For this reason, the admission is mostly based on an assessment of artistic work samples; the applicants have to show, through their work and a letter of intent, that they will have the ability to make good use of the education they will get. So even if they don't have basic qualifications for higher education (good grades at college, which is required for other courses), the school can concede dispensation of those requirements.”

Torquato (2018, 7) however observes, “Since grades are not the merit, but the 'artistic quality’ of the applicant's works samples, this could in theory be a fair process. Students with low income and with different backgrounds should have the same chances as anybody else to get into art schools. Still, the students remain white and middle class.”

Most of our interviewees agreed that artistic quality is a problematic selection criterion, and tried to unpack how the notion of “artistic quality” relates to efforts to widen participation in institutions of higher education today. What is meant by “quality”? How is the notion of quality tied to normative understandings of art, in terms of aesthetics, ways of working, subject matter, and the language one uses for one's work?

If there is a desire to diversify our art education and make our institutions more heterogeneous, it seems that the notion of quality needs to be discussed critically. Having very limited time to engage with the submitted portfolios potentially creates a risk of conflating quality with what fits into the norm. As one interviewee says:

“To some extent maybe we choose what we ‘like’ and those students may not always be the hardest workers, they may just fall into a category of working in a similar tradition that ‘we’ know. I think there is definitely bias in the process.”

(teacher)

In the conversations it surfaced that if we want to challenge the norm and break the status quo, we need to critically scrutinize our tacit understandings of what quality means in the specific context of admissions work.

“How can teachers and admission jury members, immersed in a culture that sees some outcomes as good quality and others as not, based on a white, middle-class perspective, identify the qualities of what is different? If the world-view and outcome from the applicant is based on an embodied experience that radically differs from the experience of the ones making the selection, what kind of strategies and admission criteria do we need to develop to identify those qualities?” (Torquato 2018, 3)

“Quality” is a murky and opaque word that often camouflages personal bias, taste, and individual interests. It can be used both ways, as a tool to actively or subconsciously uphold a normative status quo or to mask a sort of affirmative action by hiding the prioritization of certain applicants under the guise of quality. Quality does not only signal technical proficiency, for example. It is utterly complex, ambiguous and subjective.

Artistic quality via prep schools?

“I don’t have the exact numbers, but I would say that around 90% of the students applying to us have done a preparatory education before that. I also think that their teachers sort of prime them for how to make their applications, for example mention three references, talk about your work in this way, say that you’re really interested in the analogue facilities, etc.”

(teacher)

One interviewee links the topic of quality back to the situation with the prep schools in Sweden, arguing that the portfolios of students who haven’t gone to such schools could be seen as lacking in quality. There is likely to be a big difference between someone who has already been studying for one or two years and someone who has not. Prep school graduates seem to know how to put together an attractive portfolio and/or mobilize the “right” language.

Another teacher continues this line of reasoning, suggesting that those applicants who haven’t gone to prep school could become really strong students, but it doesn’t show in their applications and according to the current system the jury are obliged to admit the applications that display the higher quality. The system is thus pretty much set up to perpetuate this exclusion.

How, and who, is to define the criteria?

“There has been a recurrent theme that the admission criteria needed to be adjusted, so as not to select for what we already are.”

(teacher)

“We had a meeting with the jury before the admission work, but I think we could have discussed more thoroughly what the different criteria mean.”

(teacher)

Most of the interviewees referred to a lack of structure, prioritization, and resources for collectively defining a set of rigorous and fair selection criteria. It was suggested that this work should be developed in collaboration with other programmes and units.

- Current practice in one unit, one interviewee explained, is that the administration gives a list of criteria that have been used for more than ten years to the unit leader, who, in haste, picks a few without much discussion – “just in the middle of something else.” With hindsight, the interviewee noted, “We should have put more time into this discussion because the criteria we chose didn’t really help us in the admission process as well as we hoped. This is a lesson learned for the future.”

- In another unit, the criteria were apparently decided by the jury group. The programme managers, who often form part of the jury, get a mail-out once a year from the admin staff, saying, these are the current criteria, is there anything you want to change before we make them public? That is usually followed by a discussion in the jury whether the suggested criteria need to be revised. Students are not involved in this process.

- Another interviewee said, “It’s a mix of the administration checking that we’re compliant with the law and then a lot of the work is done by the programme leaders. There’s usually a long back and forth with the administration about whether what I’m saying is allowed and legally correct.”

- Another said that their criteria isn’t reviewed every year and that the person who chairs the admissions board has responsibility for the criteria. It’s not unusual that this is a conversation that only happens once or twice a year, and that it often tends to be given low priority within the institution’s everyday work.

- There are efforts made to try to re-think how the different units formulate the criteria. Some have tried to simplify and reduce the number of criteria. “We’ve tried to use a simpler and more open language, a very basic language to not make it abstract,” said one colleague.

The overall tenor of the conversations is that this work needs to be prioritized within each unit as well as collectively across units, and put on the institutional agenda in order to share experiences and learn from each other.

Almost everyone agreed that the shift from the former clunky application software to one with a much better interface for both the jury and the applicant had a huge impact, simplifying and improving the admissions process for everybody involved.

Questions to be collectively addressed

- When and why are criteria inadequate? (Some said that criteria don't work when too vague.)

- When do they work really well?

- How can we work with the criteria to be more strategic and signal that we are interested in a broad range of experiences and interests?

- How can we be clearer about what the syllabus offers and what perspectives are missing?

6. Personal Bias

Even if rigorous selection criteria are in place

“A really difficult question is, how do you make sure you’re not biased when looking at practical work?”

(teacher)

“Criteria are really important, so we know what we are discussing when looking at applications. They help to avoid the trap of relating to our own taste. Of course to some degree you can’t avoid it entirely, but when we have the criteria we have a way of guiding the discussion.”

(teacher)

One interviewee pointed out that the worst-case scenario is if you meet a student who is working with something that you don’t find interesting and because of that you’re negatively influenced towards their other qualities, in relation to the actual criteria stated. This is harmful for the process of trying to be open and attract students from completely different perspectives or backgrounds.

The admission procedures often being centred around notions of quality, creates problems as discussed above, but also, even if rigorous selection criteria are in place, how do we make sure that the notion of quality doesn’t end up being overridden by personal taste and bias?

Another teacher said they think there is a lot of personal bias at play in admissions, with teachers choosing students they “want” to work with, and that it doesn't matter how precise and elaborate the criteria are, it doesn’t prevent this.”

Not getting caught…

In her doctoral dissertation, “How does the job applicant’s ethnicity affect the selection process? Norms, preferred competencies and expected fit,” the psychologist Sima Wolgast studied different factors that could influence recruiters when recruiting from an ethnic in-group (Swedes) and out-group (non-Swedes). The study demonstrated that the recruiters, who were all Swedes, treated the applicants differently depending on their ethnicity. In an interview with Swedish applicants, the questions tended to be related to the skills needed for the job. For the other group, the questions were related to social skills and adaptability. Those whose questions were related to the job (Swedes) were perceived as “more useful” suited to the job, in detrimental contrast to the other group.

In the other part of the study, when the information was systematized and the computer made the selection, most of the out-group applicants were classified as more competent for the job. In an interview for the Swedish radio station P1, Wolgast says that if you as a person with a foreign name manage to get to an interview to begin with, there can still be a discriminatory process following you to the end.

The most discriminated against were those with Arabic names. According to the same interview, the only time persons with Arabic names weren’t discriminated against were when the recruiters were told from the beginning that if they got caught rejecting the most competent, they would have to start the process over again. Wolgast comes to the conclusion that policies to avoid discrimination and to follow up when discrimination occurs, make a difference.” (see Torquato 2018)

What about anonymous selection?

“How can we read the material if we have no idea who the person is who has made it?”

(teacher)

In the Swedish educational system, the applicants do not necessarily need to be anonymous to the selection committee, but the jury is not allowed to apply a quota based on what they know about the applicants’ background or identity. Our conversations showed that the pros and cons of anonymous admission procedures were a highly debated topic. One of the interviewees referred to a big discussion in the unit before switching to an anonymous admission process a few years ago. Some members of staff found it difficult because one wanted to make sure the “right” individual entered the institution. The profile of the school was different at the time, invested in individual authorship “pushing the boundaries”. This previous strong emphasis on the persona of the applicant seems to have shifted now more towards a focus on their work.

The understanding of who is supposed to enter our institutions seems to vary from programme to programme. It has also changed substantially in the course of the last few years. There are strong opinions that teachers shouldn’t come with a fixed idea of what kind of students they want to teach or what kind of learning is important.

In our conversations, one colleague pointed out that when doing an anonymous admission process their prejudice became useless and that was good. They claimed it was easier to focus only on the material the applicant had sent in.

However, they also said how difficult it was to evaluate the quality of anonymously submitted material, since it lacked any context.

“How can we read the material if we have no idea who the person is who has made it? [...] It was a five-minute film and if it was someone who just came from Afghanistan alone without a family, for example, and never had a camera before, then it would have been amazing to have produced that material. But if it was made by someone who has been working with film for thirty years then it wouldn't be impressive.”

(teacher)

One colleague we interviewed talked about working at another institution where they didn’t use an anonymous application process. They explained how pressure would build up the moment the admission board knew an applicant’s ethnicity, gender or class. How do you then refrain from letting that information somehow guide you in the admissions process? It’s kind of hard to get the toothpaste back into the tube, so to speak, to be totally neutral about the applicant.

7. Examples of Rethinking Admission Methods

It's not a formula

“If I was to go in tomorrow and say, ‘Let’s re-design the recruitment process for the bachelors but how would we do it?’ I guess I would make it based on the production of a short text and the production of a portfolio but I would give examples of portfolios that would range from someone putting in a mixtape to somebody putting in a collection of drawings, I would show people it could look like this but it could also look like this, to try and give a sense of breadth to give enough space for people to know it's not a formula they should be looking for, it really can be anything.”

(teacher)

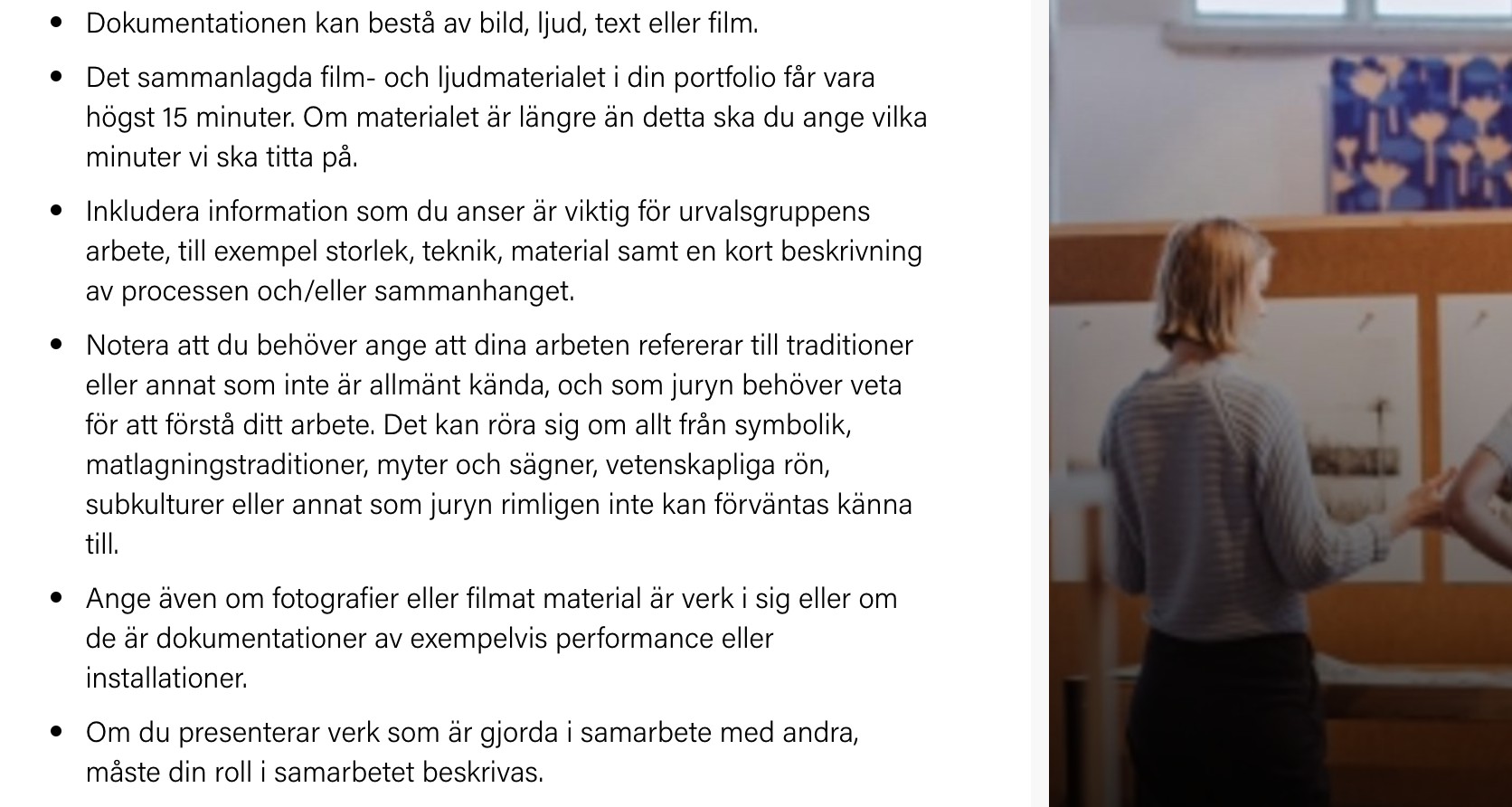

Instruction: how to compile a portfolio (excerpt). HDK-Valand BA Fine Art website

Instruction: how to compile a portfolio (excerpt). HDK-Valand BA Fine Art website

Traditionally admission is based on work samples and a letter of motivation – often alongside an interview. The above example of instructions on how to compile a portfolio caught our attention because of its de-universalizing approach, not expecting everyone involved in this process to share the same cultural, traditions and backgrounds.

"Note that you will need to indicate that your work refers to traditions or other things that are not commonly known, and that the jury needs to know in order to understand your work. This could be anything from symbolism, cooking traditions, myths and legends, scientific findings, subcultures or anything else that the jury cannot reasonably be expected to know about." (HDK-Valand BA Fine Art website: "How to compile a portfolio", translated by the authors)

Our conversations, however, did not dig into specific formats of work samples or into instructions on how to write a letter of motivation. We focussed rather on one example of the admission process being quite radically rethought at our institution, HDK-Valand, in 2018. The Literary Composition BA wanted to move away from only using work samples as selection criteria, and open up to alternatives.

They decided to admit half of the students either on the basis of their high school grades or their results in the Swedish Scholastic Aptitude Test (SweSAT). The other half were admitted on the basis of work samples. 7

The experiment was inspired by the School of Arts and Communication (K3) in Malmö, which has devoted care and effort to elaborating different pathways into higher education. But where staff in Malmö confirmed in conversations with the Literary Composition Programme in Gothenburg that this strategy was quite successful, the experiment in Gothenburg produced a different and challenging experience, as one teacher on the course relates:

“I think there are studies that support the idea that other ways of working with admissions could benefit diverse groups. What we found is that it was very hard to teach a group of students knowing that they joined the programme on different merits. The groups became very divided, those already having a writing practice on the one side, and those who hadn’t been writing at all previously on the other. This created a really big imbalance in the classroom and also many conflicts. Our analysis is that the admission process is not a quick fix. This is why we are now going back to only admitting students based on portfolio work.”

(teacher)

After this first attempt by the Literary Composition Programme to diversify the admission criteria, most of the BFA-programmes at HDK-Valand are still using work samples and interviews as their main selection criteria. However, some Freestanding Courses (Summer Courses) are now using similar methods as tested by the Literary Composition programme. For example, the base courses in film and photography are admitting students by the following structures:

-

Base course in Photography

Grades (25%), SweSat (25%) and work samples (50%) -

Base course in Film

Grades (34 %), SweSat (33 %) and academic credits, max 165 hp (33 %)

Info box Malmö K3

The School of Arts and Communication (K3) in Malmö used a wide range and different constellations of criteria to open up access to university. These constellations and percentages differ from programme to programme and include, for instance, work samples (special exams), grades, completed university credits, letters of intent, SweSAT results, interviews and special assignments:

- Culture and change: Critical Studies in the Humanities: University credits completed 100%

- Product Design: Upper secondary grades 34%, SweSAT 34%, Special exams 32%. The allocation of places in the special exams selection is based on the ranking of the work samples submitted.

- Media and Communication Studies: Media Activism, Strategy and Entrepreneurship: Upper secondary grades 66%, SweSAT 34%

- Media and Communication Studies: Culture Collaborative Media, and Creative Industries: Letter of intent/experience document 100%.

- Media and Communication Studies: Culture, Collaborative Media, and Creative Industries: Letter of intent/experience document 100%.

- Interaction Design, two-year master's programme: Applicants are selected in order according to precedence from work samples, design assignment and a letter of motivation in combination with interview if needed.

- Interaction Design, one-year master's programme: Applicants are selected in order according to precedence from work samples, design assignment and a letter of motivation in combination with interview if needed.

- Interaction Design: Upper secondary grades 66%, SweSAT 34%

- Graphic Design: Grades 34%, SweSAT 34%, special exams 32%. The allocation of places in the special exams selection is based on ranking the work samples submitted.

- English Studies: Upper secondary grades 66%, SweSAT 34%.

- Culture and Change – Critical Studies in the Humanities: University credits completed 100%.

- Communication for Development: Academic credits 20%, Letter of intent/experience document 80%.

- Visual communications: Grades 34%, Higher education exams 34%, special exams 32%.

The allocation of places in the special exams selection is based on ranking the work samples submitted.

8. The Interview

“The interview days are horrendous, but there's really no other way to do it!”

(teacher)

“The interview can be useful if structured properly and used in a particular way. It can be used effectively, but it needs consideration.”

(teacher)

Role of the interview

It is interesting to observe how differently the function of the interview is seen among our colleagues. Some think the interview is an important tool and an integral part of the process while others do not use interviews at all.

All the people we spoke to seemed to agree that the interview is the moment in the process that is most vulnerable to personal bias. This is not surprising at all because in the interview the applicant really “becomes a real person“ with all their intersecting inscriptions of gender, race, class, sexuality, ability and appearance, especially if the application process has been anonymous up until this point.

One of our colleagues described the interview as a fundamentally tricky instrument, pointing back to previous experience working at an institution in Ireland where they found that interviews were systematically biased against applicants over 40 years of age, they say:

“I think that typically what is happening in an interview is that we’re operating unconscious biases, selecting for certain things. This will depend on the mix of people in the interview panel. I think one aspect, like appearance, for example, is playing a role in the interview process. There is definitely a reproduction of the people on the panel doing the interviews.”

(teacher)

The bias could also be linked to the specific expertise and skill of the jury members because some know more than others about a particular field. “Depending on what kind of knowledge you have, you find some works more cutting-edge than others,” one interviewee says. This once again raises the question of what kind of knowledge the applicants should possess when entering into their studies? See slide Swedish Context: Prep school tradition

The way in which the interviews are carried out differs hugely between the different subjects. How many applicants are being interviewed? How much time is reserved for one interview? Are the interviews in person or online? How many interviews are conducted per day? Who is on the jury and how diverse is it?

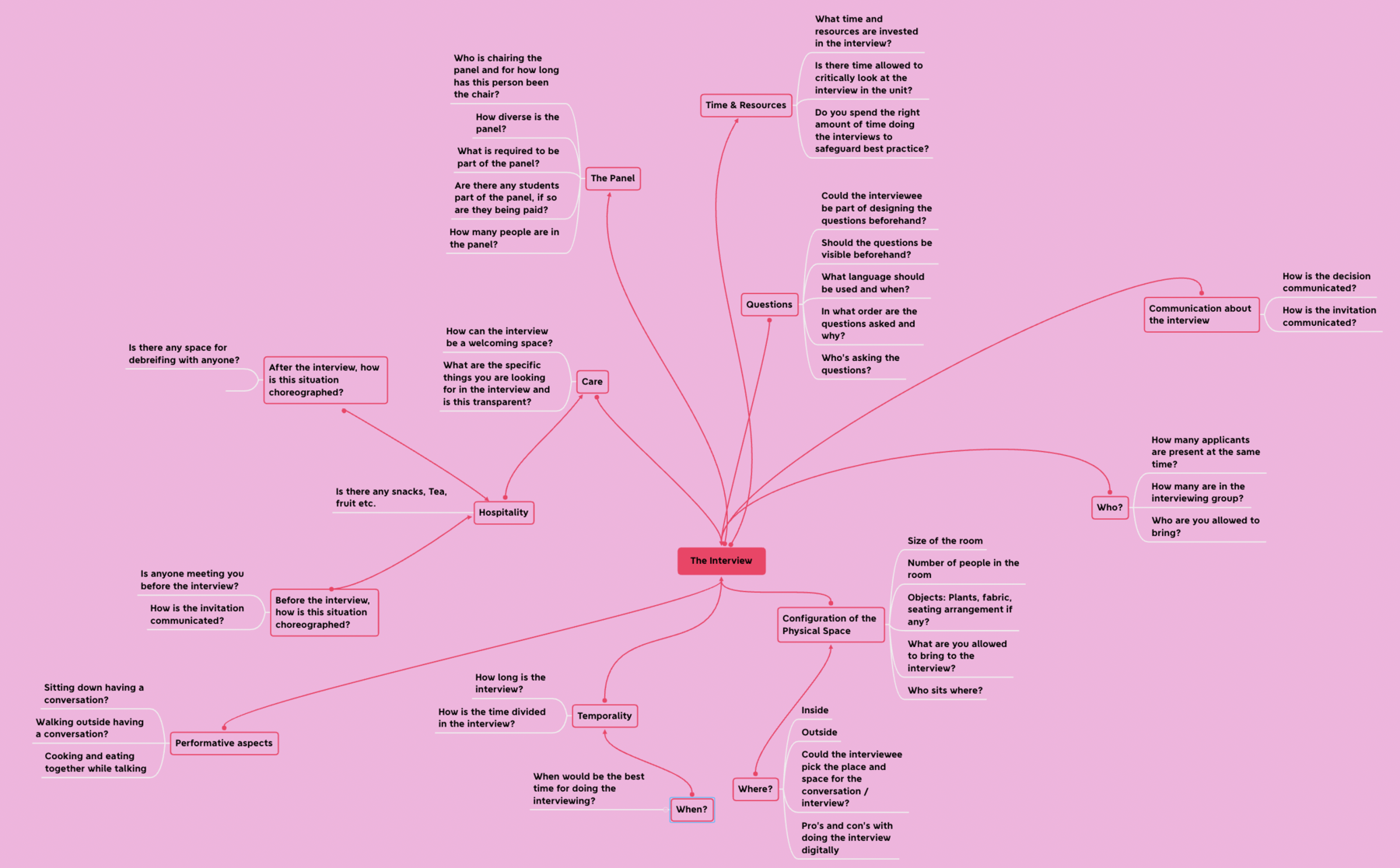

Interview: Mindmap

An early sketch by the working group to map the different aspects of admission interviews. Full screen view of the map.

Interview: Resources and Care

When thinking critically about how the interviews operate in the admissions process, three points seem most problematic: (i) The aforementioned topic of personal bias in these situations (see slide Personal Bias), (ii) whether it might be unfair to put applicants through a process that favours the more socially relaxed, outspoken and verbal, (iii) the resources that go into the interview process.

The film department describes how they usually start the interview day with four applicants in the cinema to screen one applicant’s work. One of the applicants gives feedback and discusses the work screened. Interviewers can thus see both how applicants give and receive feedback. They later discuss this in the interview with the applicants. The interview, they suggest, is also a space where teachers can find out if applicants are interested in talking about their material, because reflection and discourse forms a large part of the education programme.

Mapping the approaches of doing the interview made clear how the level of care depends on available resources:

“It’s our job in the jury to help the applicants be at their best when they are here doing the admissions. Some people need calm, some people need something else, and we need to be very attentive there. If they are very nervous, we make sure that we have time. We’re only doing four interviews every day. Normally an interview is done after 20 mins. This means that if someone is really nervous we can take a break because we have 1.5 hours for each student if there is a crisis.”

(teacher)

Other departments seem to operate on a much tighter budget when it comes to time and resources:

“Altogether we were interviewing 53 persons, and it was three days so it was around 15-17 interviews a day. This year, during the pandemic, the interviews took place online. They were a bit shorter than usual before the pandemic. Now they were only 10 mins to accommodate the zoom fatigue of the jury.”

(teacher)

For other interviewees it was unclear to what extent the interviews are beneficial, whether they are fair and actually necessary for their programme. Some of them have ongoing discussions on whether to stop doing interviews at all because it's not always clear what you gain from them. There is the suggestion that it puts the applicants in a vulnerable situation: “You can be very nervous, you can be sick, or maybe you just have a bad day. Perhaps you are not so socially excellent. We shouldn’t pass a judgment on that.” Within the Literary Composition programme, for example, there is a risk that not everyone who writes might be able to perform well in an interview, or feel comfortable speaking about their work and such an interview situation could therefore be unfair. Because of this, they don’t do interviews at all as part of admissions.

“We want them to develop their conversation skills in class, in a safe environment, and we don’t want to put them in front of a teachers' committee to do that. But we’ve been thinking about doing some sort of workshop instead to see people in action. That is something for the future.”

(teacher)

Another programme leader pointed out that an applicant’s ability to perform, to sit nervously in a pressured interview situation, that specific skill set is not something artists need in Sweden.

Interview: Scene “Eve Democracy”

Scene “Eve Democracy”, in“Sympathy for the Devil/One plus One by Jean-Luc Godard. Starring: Anne Wiazemsky, 1968

Interview: a two-way communication

“However, when not doing interviews, we are lacking this moment of encounter where students can ask questions about the programme. Therefore, the Literary Composition programme is considering an FAQ section on the homepage, or an ‘open hour’ slot for people who want to ask questions before or during their application.”

(teacher)

The interview situation, it became clear, is not only an occasion for the jury to query the applicant but equally an opportunity for the applicant to meet the team and ask questions. Therefore, interviews could also be seen as an important mutual communication channel between applicant and institution.

We see a range of opinions on the subject. There are units that invest lots of time and resource on interviews, and are confident about their function. Others do them but are beginning to question their usefulness and gravitate towards changing them radically or stopping. One programme has never done interviews – and is convinced that is right.

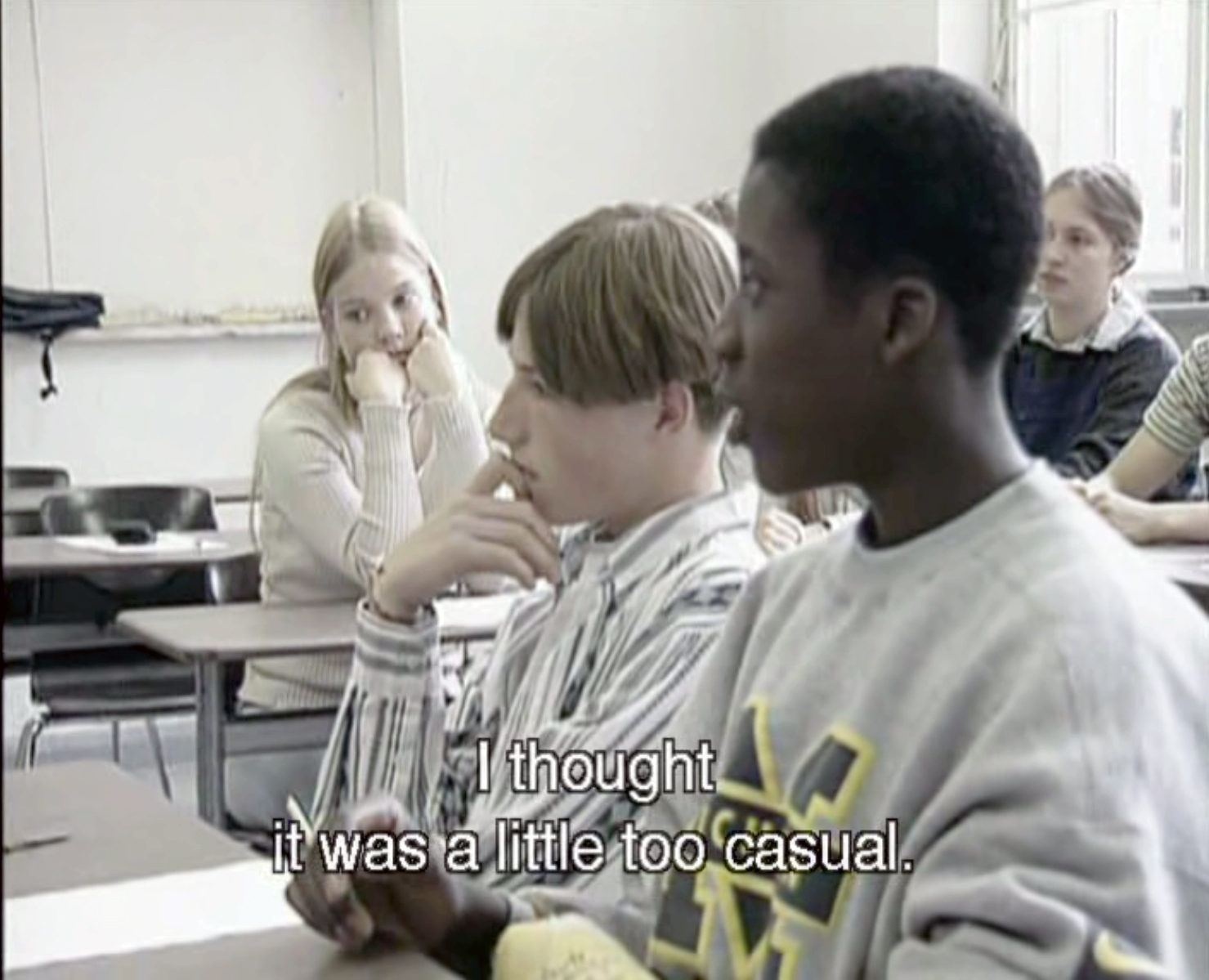

Harun Farocki: The Interview

Stills from Harun Farocki's film, “The Interview” (Die Bewerbung) shot in the summer of 1996, when Farocki and his team filmed in a range of job application training courses in Germany. "School drop-outs, university graduates, people who have been re-trained, the long-term unemployed, recovered drug addicts, and mid-level managers – all of them are supposed to learn how to market and sell themselves, a skill to which the term “self-management” is applied.” (Farocki 1996) Watching these students practicing step by step the interview process and training how to present themselves, awkwardly underlines the performative aspect of the application process: How to present oneself as the "right fit" and how to succeed in an interview when the conversation is not a negotiation but a one-way interrogation?

Interview: Jean Genet interviewed by Nigel Williamson

Jean Genet interviewed by Nigel Williamson for BBC 2 in the summer of 1985. London, BBC Arena. Watch recording here

Jean Genet interviewed by Nigel Williamson for BBC 2 in the summer of 1985. London, BBC Arena. Watch recording here

Transcript

Jean Genet: I had a dream last night. I dreamed that the technicians for this film revolted. Assisting with the arrangement of the shots, the preparation of a film, they never have the right to speak. Now why is that? And I thought they would be daring enough — since we were talking yesterday about being daring —to chase me from my seat, to take my place. And yet they don’t move. Can you tell me how they explain that?

Nigel Williamson: Yes. Uh… How they…?

JG: How they explain that. Why they don’t come and chase me away, and chase you away too, and then say, “What you’re saying is so stupid that I really don’t feel like going on with this work!” Ask them.NW: Okay, sure. (He speaks to the technicians and translates Genet’s question into English.)

JG: The sound man too.NW: (Nigel Williams asks the sound man, Duncan Fairs, who answers that he doesn’t have much to say at the moment, that the people who work every day lose their sense of objective judgment about what they’re doing and remain prisoners of their personal world. He adds that the technicians always have something to say after the filming, but that if they spoke in front of the camera it would cost a lot of money and would be very expensive for the film production company.) Is that what interested you about your dream: disrupting the order of things? In a certain way you wanted to disrupt the order that exists in this little room?

JG: Disrupt the order of things?NW: Yes.

JG: Of course, of course. It seems so stiff to me! I’m all alone here, and here in front of me there are one, two, three, four, five, six people. Obviously I want to disrupt the order, and that’s why yesterday I asked you to come over here. Of course.NW: Yes, it’s like a police interrogation?

JG: There’s that, of course. I told you — is the camera rolling? Good. I told you yesterday that you were doing the work of a cop, and you continue to do it, today too, this morning. I told you that yesterday and you’ve already forgotten it, because you continue to interrogate me just like the thief I was thirty years ago was interrogated by the police, by a whole police squad. And I’m on the hot seat, alone, interrogated by a bunch of people. There is a norm on one side, a norm where you are, all of you: two, three, four, five, six, seven, and also the editors of the film and the BBC, and then there’s an outer margin where I am, where I am marginalized. And if I’m afraid of entering the norm? Of course I’m afraid of entering the norm, and if I’m raising my voice right now, it’s because I’m in the process of entering the norm, I’m entering English homes, and obviously I don’t like it very much. But I’m not angry at you who are the norm, I’m angry at myself because I agreed to come here. And I really don’t like it very much at all.

9. Fitting — Who fits whom?

What does it mean to “fit” an institution?

“In terms of fitting, yeah, it’s like: can the student fit the structure of how the school is operating and how the learning activities are designed? We need to somehow accept students according to that. I’m not saying it's right or wrong, but if we accept a student that cannot fit into this academic structure, then it will result in a domino effect where students won’t pass exams, and we need to re-examine them. Then it's just like a domino effect of extra work.”

(teacher)

“When it comes to fitting, I understand that we don’t want people to feel sad and lonely for three years of their studies. But what do we actually mean by fitting or not fitting?”

(teacher)

“In many ways I think the applicant needs to fit the programme but maybe not the institution generally. Of course we want to be a programme for everyone, open to every person, but we can’t be open to every idea, we can’t be open to everything.”

(teacher)

“You need a joke”

Roleplay 01: “You need a joke” (2020). With André Alves, Andreas Engman, Inga Kolbrun Söring, Eva Weinmayr, Lucy Wilson

To dig deeper into the question of fitting/not-fitting, the working group ran a series of exercises in which – with the help of occasional guests – role-play interview situations were improvised both irl and online.

“We need a duo”

Roleplay 02: “We need a duo”. With André Alves, Rose Brander, MC Coble, Andreas Engman, Eva Weinmayr.

Some colleagues claimed that the interview moment is as much about finding out if the institution is a good match for the applicant as vice versa. So the interview is an important moment for giving information about the programme, specifying what the students will encounter, explaining what education is on offer. It is also a way of making sure that the applicants understand what kind of contract they are entering into with the institution.

One important focus of our conversations was the specific role of the interview in finding out what it means to fit an institution. We got hooked by the question of who fits whom: the prospective student, the institution or the institution, the student? Do you fit because you are clearly a part of the existing norm – thinking and looking like most of the people in the school? Or do you fit the desire of the institution because you are a person who is expected to break that norm?

Sanna Samuelsson's (2016) claim that “artists and filmmakers with a different background than white middle class, had […] difficulties of getting into art schools or getting funds from art institutions when trying to do something that is not related to the colour of their skin or to their background” 8 leads Torquato (2018, 8) to speculating that these artists and filmamakers are being accepted into a white institution only if they deal with issues related to ‘otherness’ in a way that fits the white idea of ‘otherness’.

Loosening the tight fit: aftercare

“I think a fundamental question is how we look after the students that don't “fit” when they have been admitted to the institution. There has to be a really good conversation about this.”

(teacher)

“A really important question is, how can we make the group of people applying to our programmes more diverse? What do we need to change in-house when it comes, for example, to teacher recruitment, or to teaching and reading references etc.? This is a huge amount of work!”

(teacher)

“The walls are not only the application process and later the jury and the interview; it continues after you have been admitted. A good example is a former student from Syria. The language of art is different in Syria compared to, say, the UK or Sweden. He had a way of explaining his paintings that didn’t match the language being used in the institution and this made an extra barrier for him. But he could take the same painting to other institutions in Syria and they would all understand him. This problem is super messy."

(teacher)

What turned out to be a major question mark was the “aftercare” that can be provided, for both admitted students and teachers. Imagine a scenario where different opinions, convictions or beliefs clash in a classroom because of its diversity. All players need to be equipped to create and hold this space for dissent and potentially emerging conflicts. It has been said we need a better support structure and development opportunities, like workshops, mentoring to supervise teachers and students that have to negotiate and confront hidden and open conflicts and make sure that learning is still possible.

10. Propositions for the Future

(A) Action point: Make panels and juries more diverse

“When those who have the power to name and to socially construct reality choose not to see you or hear you… when someone with the authority of a teacher, say, describes the world and you are not in it, there is a moment of psychic disequilibrium, as if you looked in the mirror and saw nothing. It takes some strength of soul —and not just individual strength, but collective understanding – to resist this void, this non-being, into which you are thrust, and to stand up, demanding to be seen and heard.”

(Rich, 1986)

“To be able to see yourself in the teaching and the teaching body is super important. I had a student from Afghanistan one day she came and said, ‘Do you know how happy I am that you are in this building?’ ‘What do you mean?’ I said. She said, ‘I don’t see myself in this whole building, when I see you I understand that someone with a different look has been accepted here and that means that maybe I also can be accepted here.’”

(teacher)

(A) Suggestions

Idea 1: Create non-homogeneous jury panels

Make sure you are looking at a diversity in the recruitment panel to match the diversity you’re seeking. It might require a little extra effort by the head of jury to compose non-homogeneous jury panels. This responsibility of composing the jury should not be taken by the same person year after year.

Idea 2: It is good practice to invite external jury members

Externals will enrich the diversity with a range of experiences not present with the body of staff.

Idea 3: Keep inviting a student representative to be part of the admission process

Student representatives can add a different perspective.

(B) Action point: Who are we addressing and how do we encourage people to apply?

Behjat remembers when he was encouraged to apply to a BA programme in the UK: “I was totally freaked out about it.”

(B) Suggestions

Idea 1: Simplify the technical requirements in the admission process

One interviewee observed at the Stockholm-based art school Konstfack that the first round of the application process comprised a wide range of people with all sorts of experiences and backgrounds. However, closer to the end of the selection process, when applicants had to upload several documents and were facing technical challenges, this changed. This could also be seen as a form of discrimination.

Idea 2: Offer introductions to explain the process step by step

The admission process tends to be designed in a way that some people will understand, but others will find difficult. The crucial task is to explain the admission process simply. Then people will be more confident in entering our institutions.

Idea 3: Employ a contact person with pedagogical and technical skills

It has been suggested by one of our colleagues that a person be employed to whom every applicant can turn to if they have questions regarding admissions. This person should be very skilled, with pedagogical and technical experience and knowledge that can guide people through applications.

Idea 4: Be clear about mutual expectations

One point of encounter is, of course, the art school’s website and the page for the programme in question. In the self-description, it should be clear what the institution is offering in terms of educational structures and frameworks. It should also be clear what the institution expects from prospective students and what kind of contract the student is entering into with the institution. This needs to happen both on the webpage and in the interview.

Idea 5: Give examples of portfolio work to show a breadth of possibilities

When giving instructions about submission of work samples, make it clear the admissions board isn’t looking for one specific formula, it really could be anything. [link to prep school slide]

Example: Open Call for Applications to TTTT

The following example shows how the concept of work samples or portfolio has been expanded in the context of the TTTT programme. With the “Open Call for Application” we wanted to broaden the notion of what constitutes a “portfolio” or a “letter of motivation” by shifting the concept from “artwork” to “practice”. We arrived at the following structure for explaining what kind of material could be submitted.

How to Apply to the TTTT programme, part of the Call for applications, published in October 2019.

How to Apply to the TTTT programme, part of the Call for applications, published in October 2019.

(C) Action point: The admission work starts with outreach

“When trying to attract new applicants, we should seek out constituencies that are not already represented in our institutions. We need to connect more with a wider range of possible applicants in society. We need to spend a good amount of energy on reaching kids in school when they are younger to introduce what it means to work with and study art.”

(teacher)

“…interviewing 50 applicants and with two people doing the interviews – that would be like two months of full-time work going into admissions… That seemed to me to be too much work...more work going into that selection point than going into the information point to encourage people to apply."

(teacher)

(C) Suggestions

Idea 1: Invest less time on recruitment, more time on outreach

Putting less time into recruitment and investing more time reaching out and encouraging people (mostly marginalized groups) to apply, as one interviewee proposed.

Idea 2: Map out whether the strategies of address are working

Mapping the amount of published information and knowledge about the programmes. Are the strategies of address working? Because, as one teacher said, it is a problem “if we are invisible to those who want to see us, and if we are standoffish to people who want to come into contact with us and study here.”

Idea 3: Organize an “Open House Day” at the art academy

Inviting curious new groups to an "Open House Day" to walk through the – more often than not – heavy entrance door, to walk around the building, take part in workshops, look at exhibitions, get first-hand information about programmes and activities. For example, in photography, the programme responsible said “We did this workshop at Open House, where they did these massive silhouette self-portraits in the analogue darkroom and then they had an exhibition in Galleri Monitor. So they really got some idea: okay so that's what you do here. It's to make this place not so unapproachable.”

Idea 4: Open House brought to other communities

“Open House” activities could be brought to other buildings in town, a library, for example, or a cultural centre, where workshops could be run.

Idea 5: Hold workshops in the segregated periphery

Facilitating courses and creating spaces for encounter outside the academy. This could be, for example, that students go to high schools in segregated neighbourhoods to talk about the programme and their’ experiences of it. At HDK-Valand we had some activities of students running acting and filming workshops, and a collaboration between the Fine Art department and a preparatory school in Angered, a segregated neighbourhood in Gothenburg.

Idea 6: Create exchange programmes reaching out to foreign schools

One example is the exchange programme between HDK-Valand film unit and Wits University in Johannesburg, South Africa that expands the set of teaching and learning experiences for both sides, as one colleague shared, and helps with re-evaluation of the department’s own values.

Idea 7: Summer courses

Another possible point of encounter are the ten-week summer courses at HDK-Valand offered by the different programmes on a range of topics ("Introduction to Contemporary Art and Politics", "Digital Photography Introduction", “Art and Politics on Friendship and Political Imaginary", “A Feminist Witch School,” “Trojan Horses”). The admission process here tends to be lighter. Exact requirements vary from course to course, but commonly it asks for fewer works in the portfolio and a shorter letter of motivation. Often, participation in a summer course is a bridge to full-time study at the art academy.

Idea 8: Offer a Base Course as an introduction to the BA programme

A number of units offer base courses to reach out to applicants other than those who usually apply. These courses could work as a way of opening up the institution, widening participation and creating a space to get to know a specific subject and how the academy teaches it. There is, however, the same risk with these courses as with any other programme, namely that it is profiled to the institution’s traditional constituencies.

(D) Action point: Create sustainable initiatives to desegregate our institutions

"The work of desegregating our institutions should be assigned to a bigger working group. Work like this is usually assigned to one person such as the diversity officer or that one teacher who has it as an extra assignment. This is not a very sustainable model."

(teacher)

”The turnover of staff and the student body within the institution is completely transforming in just a number of years, so that means that any project or activity if it's only attached to one to two people it is very vulnerable.[…] An obstacle has been the difficulty of transferring an agenda from a small number of people so that it belongs to the wider group. If this work is too person-centred and not sufficiently spread it becomes an obstacle. Effective advocacy within the core constituency is important.”

(teacher)

"It would be good if someone from the admissions department could advise on these things and lead it rather than each department trying it out in their own way.”

(teacher)

"I don’t think we’ve had such a lively discussion about this. It feels as if it is very much up to each programme to work with this, and I would say that we have not worked with it at all.”

(teacher)

(D) Suggestions

Idea 1: Depersonalize the work of desegregating our institutions — Institute protocols

Any project or activity only attached to one or two people is vulnerable because it is lacking continuity. If this work is too person-centred and not sufficiently spread across the staff, administration and leadership body, it becomes an obstacle. Effective advocacy within the core constituency is important.

Idea 2: Create a diverse team leading the process of instituting new protocols

Create a team consisting of an archivist, alongside, for example, admin, teachers, leadership. Being aware of the current and past protocols in order to not repeat problematic structures from the past. As one interviewee observes, “We inherit, then we repeat because we don’t have time to update anything or go through it properly.”

Idea 3: Create spaces where disagreement is possible

Those in leading positions should be able to create a legitimate space for disagreement with colleagues, a space where productive disagreement is sought after instead of striving for consensus, a space where disagreement is valued rather than punished. Such a structure would enable teaching staff from different programmes to work together in ways that go beyond staff members’ individual differences and interests. In that way, it might be possible to create the openness and trust necessary for experimentation and development – a prerequisite for transformative work.

Idea 4: Allocate resources and time

Put admission processes at the top of the agenda in the institution’s day-to-day work. It has been stressed by the teachers we spoke to that this work should not come from the teaching budget. The required time and resources should be financed outside the day-to-day operating budget.

Idea 5: Don’t look at desegregation as “extra” work

Institutionalize protocols for collective desegregation processes, so they become the norm in the institution and not “extra” work that therefore becomes deprioritized and under-resourced.

Idea 6: Create a common agenda

Foster a cross-unit vision and communicate possible ways of rethinking admissions policies. Develop overarching protocols that could serve all units sustainably.

(E) Action point: Remove the jury process altogether

“My suggestion is to remove the jury process altogether or somehow find a different way to do it. If we have 450-500 applicants, I can imagine a jury selecting down to a 100 really easily, the level of agreement within the jury to select these hundred is about 99%. I think everybody would agree. So once we have these hundred selected, we should do the lottery!”

(teacher)

(E) Suggestions

Idea 1: Don’t do juries, do a lottery

In order to get rid of the competitive admission process it has been suggested in our conversations that a lottery replace the selection process. One example would be San Francisco’s elite Lowell High School, which stopped doing merit-based admissions for their ninth-year class in 2021 and opted to use a lottery instead. Irene Lo, Assistant Professor of Management Science and Engineering at Stanford University, says Lowell saw a shift that can be completely attributed to the new admissions policy: this year’s ninth-grade class will have more Black and Hispanic students combined than at any time in the last 25 years. Lo has worked with San Francisco education officials to create a new and more equitable assignment system for all schools in the district, and says that the lottery system appears to give everyone an equal chance. (Talley 2021)

Implementing such policies in Sweden, of course, would mean all schools would have to agree a joint procedure. But would the lottery be an acceptable strategy for applicants who have already invested years in preparatory school?

Check-out

“The one thing I would say is, I think we are irrevocably set upon a course. It can stall, there can be a bit of backsliding, but I don’t think there’s any going back. We’re not going back to an institution that prides itself on servicing a small elite. We’re not going back there!” (teacher)

This text is a way for us to share the conversations we had in our art school, (HDK-Valand, Gothenburg) on the demanding but crucial mission to widen participation in arts education. It aims at creating a more resilient structure in the daily life of our institutions to have such conversations. It also shares some concrete practice examples in the “propositions for the future” chapter.

Instead of quick bug fixes, we hope this text will support the reader to look at their admission practice with a fresh eye. We want to suggest that some of these practices that tend to be grounded in inherited norms and traditions need to be unpacked and revised – on a personal and institutional level – in order to create inclusive institutions.

References

- “Art.School.Differences” end report by Philippe Saner, Sophie Vögele und Pauline Vessely, in cooperation with Tina Bopp, Dora Borer, Maälle Cornut, Serena Dankwa, Carmen Mörsch, Catrin Seefranz and Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa [German/French] Download PDF.

- Edling, Marta. “Att förbereda för rummet av möjligheter: om skolornas antagning, fria utbildning och starka fältberoende”. In: Martin Gustavsson, Mikael Börjesson, Marta Edling (ed.), Konstens omv nda ekonomi: tillgångar inom utbildningar och fält 1938-2008 (pp. 67-81). Göteborg: Daidalos, 2012.

- Farocki, Harun. “Die Bewerbung” (The Interview), film, 58 min, Germany, 1996.

- Genet, Jean and Nigel Williamson interview. London: BBC Arena, 1985. Watch recording

- Genet, Jean, transcript of interview by Nigel Williamson. London: BBC Arena, 1985. Institute for Experimental Arts blog

- Godard, Jean-Luc. “Sympathy for the Devil/One plus One ”, 1968. Scene: Eve Democracy, YouTube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mtb3gNSf4Gw

- HDK-Valand, Academy of Art and Design, University of Gothenburg. Webpage

- K3, School of Arts and Communication, Malmö

- Library of Congress, Global Legal Monitor, “Brazil: New Quota Law Reserves 50% of the Places at Federal Universities for Public School Students”. 2012. Web Page

- “Open Up”. Webpage, 2020-2023

- Rich, Adrienne. Blood, Bread, and Poetry: Selected Prose, 1979-1985. New York and London: Norton, 1986.

- “River of Light” Mission Statement, 2017 – ongoing. River of Light procession on February 20, 2017 (Social Justice Day). YouTube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ys2vr0DWK-E

- Samuelsson, Sanna. “Det Vita Havet” — ur Konstnären no 1, 2016 Konstnärernas Riksorganisation, 2016

- Talley, Emma. “Lowell got rid of competitive admissions. New data shows how that’s impacted the school’s diversity.” In San Francisco Chronicle, August 26, 2021. https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Lowell-got-rid-of-competitive-admissions-New-16415271.php#photo-21398545

- Torquato, Cecilia. “The Reorientation of Fairness in Higher Education — a brief look into the Brazilian quota system and social and ethical inclusion in art schools in Sweden,” University of Gothenburg, 2018 Download PDF

- Vögele, Sophie with Gianna Brühwiler, Şebnem Efe and in cooperation with Peter Truniger. “Address! Students with migration experience at the Bachelor Art Education (BAE), Zurich University of the Arts ZHdK. Identifying inclusive measures in the application and recruitment of candidates of the BAE programme at the ZHdK. [German] Download PDF.

- Vögele, Sophie. presentation at IRVAS conference: “Tomorrow's Classroom” at Head Geneva, 28.1.2016, in: Let's Mobilize: What is Feminist Pedagogy, HDK-Valand, 2016, Download workbook PDF

- Vögele, Sophie and Gianna Brühwiler, Şebnem Efe in cooperation with Peter Truniger. “Address! Students with migration experience at the Bachelor Art Education (BAE), Zurich University of the Arts, ZHdK”, 2018. [German]Download PDF

- Vox: “What we get wrong about affirmative action”, Dec 10, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HuUDhfKV3bk

- Wolgast, Sima. “How does the job applicants’ ethnicity affect the selection process? Norms, preferred competencies and expected fit,” Lund University, 2017. Download PDF

-

“The attribution “teacher” refers to quotes from the conversations we conducted with colleagues at HDK-Valand. See “Methods”. ↩

-

The study was carried out between 2015–18 at the Institute for Art Education (IAE), University of the Arts Zurich (ZHdK) in cooperation with Haute École d’art et de design – Geneva (HEAD – Geneva), Haute École de musique, Geneva (HEM – Geneva). See also: “Address! Students with migration experience at the Bachelor Art Education (BAE), Zurich University of the Arts, ZHdK" that identifies inclusive measures in the application and recruitment of candidates of the BAE programme at the ZHdK. ↩

-

“River of Light” (ROL) is a non-profit association based in Boras/Gothenburg in Sweden. ROL is an independent, non-political and non religiously affiliated association and its mission is to provide opportunities for innovative, creative and social engagement. The vision is for an inclusive society where there is respect for difference and everyone lives equally and free from discrimination.

Marking the 150th anniversary of Valand Art Academy, the project was initiated by artist Behjat Omer Abdulla in 2016, in the belief “that creativity and working with artists can accelerate the process of integration especially amongst unaccompanied minors and their Swedish peers. ROL is home to a diversity of people and ideas, and reflects a spirit of inclusiveness, a global perspective, and the cultivation of integrity, compassion, civility and ethical behaviour as foundational to living well together.” Mission statement.

The activities that took place at HDK-Valand were, for example, lantern-making workshops, which served as meeting points in the community for new arrivals and Swedish young people and families. Here art operates as a tool to break the boundaries of language, geography and cultural divisions, and thereby bring together people from all kinds of backgrounds, who would not normally meet.

The workshops were followed by a procession through Gothenburg town centre on United Nations Social Justice day (February 20, 2017). The project is ongoing. ↩↩ -

Open Up is a four-year cultural project (2020-2023), co-funded by Creative Europe, that aims to promote underrepresented artists, designers, craftspeople and performers located in the seven cities of the partner organizations. It furthermore aims to establish sustainable art practices amongst them, by providing the participants with training and knowledge through the project’s various actions, which include laboratories, workshops, festivals and exhibitions. Open Up aims to empower creators to develop their skills, present their works and create new business models that will enable them to sustain their work even after the end of the project. Open Up webpage ↩

-

"Affirmative action refers to a set of policies and practices within a government or organization seeking to include particular groups based on their gender, race, sexuality, creed or nationality in areas in which they are underrepresented such as education and employment. Historically and internationally, support for affirmative action has sought to achieve goals such as bridging inequalities in employment and pay, increasing access to education, promoting diversity and redressing apparent past wrongs, harms, or hindrances.

The nature of affirmative action policies varies from region to region and exists on a spectrum from hard quotas to merely encouraging increased participation. Some countries use a quota system, whereby a certain percentage of government jobs, political positions, and school vacancies must be reserved for members of certain groups." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Affirmative_action

What we get wrong about affirmative action, Vox: Dec 10, 2018 ↩ -